“The Sun was shining during that first Exodus touchdown. Some got down on their hands and knees and kissed the concrete. Others simply burst into tears where they stood, while others lay on the grass and sobbed. I was thunderstruck…“, words of RAF pilot Philip Gray (From ‘The Great Escape: A Canadian Story‘ By Ted Barris) who flew repatriation flights as part of the Operation Exodus. These words in a nutshell encapsulate the amount of emotion that the POWs (prisoners of war) packed within them during the four, five or six year period that they spent in the German stalags as prisoners.

Operation Exodus was an Allied repatriation operation, which was executed during the closing stages of the Second World War, to bring back Allied POWs cut loose from various prison camps across the Reich. After the liberation of the prison camps by allied forces, thousands of ex-POWs who were released had to be bought back to Britain, and RAF command employed bomber planes to repatriate them. A total of more than 16000 ex-POWs were repatriated as part of Operation Exodus. It was in one such flight, during early May 1945, that the Royal Canadian Air Force Bomber Pilot, Kingsley Brown, an ex-POW was repatriated to Britain.

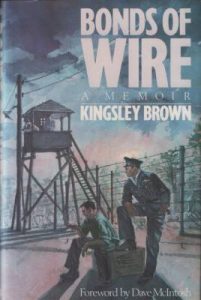

‘Bonds of Wire’ is a narrative of Kingsley Brown’s experiences as a Prisoner-of-War at the famous Luftwaffe-run prison camp Stalag Luft III (famous for the escape plots ‘Wooden Horse’ and ‘The Great Escape’) during World War II. But unlike the other POW stories from the time period, ‘Bonds of Wire’ is quiet different, as throughout the narrative the author is trying to identify and highlight moments of kindness and humanity that he encountered from his enemies during his three year incarceration at the POW camp. For Kingsley Brown these wonderful moments of ‘humor and compassion’ were important, as they were quiet instrumental in his survival during terrible times at the camp.

Kingsley Brown‘s journey to the Stalag Luft III

When he was shot down on July 3 1942, over Holland by a German Messerschmitt night-fighter, RCAF Bomber pilot Kingsley Brown was expecting that his constant thoughts of danger, fear, suffering and even death that accompanied him during his days of active combat duty were finally going to catch up with him as a prisoner at the hand of his enemies. After his capture Kingsley Brown was initially taken to a German barracks in the Dutch town of Staveren and from there he was transported to the ‘Leeuwarden’, one of the major Luftwaffe fighter bases in Holland during that time.

After some more shifting about, he along with other captured air force men were transported to the Stalag Luft III POW camp. From the moment of his capture to his arrival at the Luftwaffe camp at ‘Zagan’, Kingsley Brown encounters officers and soldiers of the German army who are friendly to a point, and with ‘humor’ and understanding he was quiet able to melt the ice between him and his captors. The way in which they treat him with dignity and even kindness in response to his gentle behavior acts as a moral booster for him, and gives him that single spark of ‘inspiration’ that acts as a beacon for any human being to traverse an ocean of desperation and awfulness without going insane.

Kingsley Brown meeting with a German officer who lost his son to Allied bombing; the guards while escorting him to Amsterdam providing him with a seat in first-class, because of him being an officer; him having an amusing conversation about ‘Pied Piper’ with his guards while traveling through Hameln are some of the interesting moments from his narrative until his imprisonment at the Stalag Luft III.

His days at the Stalag Luft III

In the initial days of his life at the Stalag Luft III camp, he becomes a member of the group of officers who are assigned with the duty of forging documents and permits for those who are aspiring to escape from the prison camp. After a few months of propaganda and document forging efforts, Brown and a fellow air force officer named ‘Gordon Brettell’ manage to escape by hiding among some new constructions happening in the camp. But after three days of desperate traveling they get re-captured at Chemintz and are send back to the Stalag Luft III. Gordon Brettell was later murdered by the Gestapo at Danzing after participating in the epic ‘Great Escape’ of 1944 from Stalag Luft III.

Another attempt by Brown along with Joe Ricks, an RAF flight lieutenant, to escape the camp by switching identities with two prisoners from Stalag VIII-B in Lamsdorf also results in a failure. While reading the narrations of his days at the Stalag Luft III, the reader can glimpse some of the finest examples of human mind seeking and finding sanity & normalcy from simple acts of kindness during a time of utter chaos and anxiety. During his transportation back to Zagan on train after his re-capture at Lamsdorf, he encounters a group of German officers and school teachers returning to Berlin for Christmas. Brown’s descriptions of how these fellow travelers, his guards and himself created some moments of happiness by singing songs and carols and sharing anecdotes about Canada is a perfect example for the capability of human beings to find happiness even during the apex of desperation.

Soldiers adorning different sets of uniforms and fighting for different ideologies becoming mere human beings can be glimpsed in another incident shared by Brown. After their capture at Lamsdorf, Brown and Joe are put in solitary confinement. On the Christmas day of 1943, a group of German prison guards secretly take both Brown and Joe to an orderly room and allow them to listen to the Christmas greeting from King George VI over radio as a Christmas present.

The historic importance of Browns narrative

Brown’s narrative gains importance from a historic perspective due to the fact that as a resident at the Stalag Luft III during early 1945 Brown was perfectly in a position to narrate the end of the Nazi era happening around him in great detail. When the pressure from an advancing Russian army becomes too much, the POWs at the camp are evacuated by the guards and are forced to march with masses of retreating German units in a great migration – the death march – across Germany, fighting the threats of both the harshest of the winter and a capture by the Russian army.

The descriptions of prisoners as well as the retreating German units sharing farmyards at night, the civilians sharing whatever meager food supplies they have with the prisoners, some of the fellow prisoners perishing to the mental and physical strain of the march across harshest of conditions are all presented in detail by Brown. After days of marching on open roads, the prisoners were taken to the infamous Stalag III-A prison camp in Luckenwalde. Finally on April 20th 1945, the Russian offensive becomes too hot for the remaining German forces and the guards at the Stalag III-A lock the prisoners inside the camp and abandon their posts. On April 22nd Russian tanks burst through the barbed wire fences surrounding the camp at Luckenwalde to liberate the prisoners of war and along with them Brown.

Of all the POW narratives and POW escape documents I have read from the World War II, ‘Bonds of War’ was a book that was quiet surprising with the amount of positiveness and cheerfulness that Kingsley Brown discover during such a terrible time as a prisoner. By preparing his mind to welcome the unexpected, Kingsley Brown overcomes hostilities of wartime through humor, warmth, kindness and acts of friendship shown towards his enemies, which surprisingly gets reciprocated in many unlikely occasions. It was quiet inspiring to see Kingsley Brown even when engulfed in the gloom, sorrow and fear of the imprisonment and death happening around him carefully picking and cherishing each moments of cheerfulness – even if they are minute – as elixirs for survival.

A fascinating narrative both as a historic document and as an inspiring story, which can be enjoyed by both World War II history enthusiasts and generic fans of exciting real life stories.

Cover Image: Liberated POWs walk out to Lancaster bombers at Lubeck aerodrome, waiting to fly them home to Britain, 11 May 1945 as part of Operation Exodus. From the collections of the Imperial War Museums.