And not only do the ghosts themselves always walk on Christmas Eve, but live people always sit and talk about them on Christmas Eve. Whenever five or six English-speaking people meet round a fire on Christmas Eve, they start telling each other ghost stories. Nothing satisfies us on Christmas Eve but to hear each other tell authentic anecdotes about spectres. It is a genial, festive season, and we love to muse upon graves, and dead bodies, and murders, and blood.

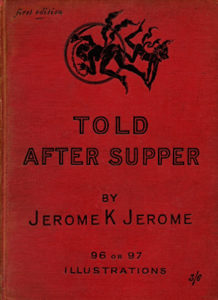

In the introduction of Told After Supper, originally published in 1891, the English writer and humorist, Jerome K. Jerome, describes the Victorian tradition of telling ghost stories on Christmas Eve, and why he chose it as his setting for narrating a string of lightweight ghost stories. Written with a healthy dosage of humor, these short stories, which are almost like pastiches of the traditional Victorian era tales of supernatural, offer a relaxed reading experience.

Within this anthology, the author employs a frame narrative technique to unfold a series of short funny ghost tales within the setting of events from a Christmas Eve get-together. It is told from the perspective of a narrator, who is visiting his uncle’s family for Christmas. The guests, after having the supper and indulging in large quantity of drinks, engage in sharing ghost stories with each other and each of these stories are described to the reader through the narrator.

These short funny stories are quiet pleasant to read and can be enjoyed in a single sitting. Jerome K. Jerome’s signature humor and the cheerful approach that he employs while narrating a story can be observed within this funny, not scary anthology of ghost stories.

The forgotten tradition of telling ghost stories on Christmas Eve and Christmas season

In Victorian England – and most probably in the centuries before that – the nights of the season of Christmas was believed to be the most holy as well as the most haunted.

In Christmas in ritual and tradition, Christian and Pagan , published in 1912, author Clement A Miles observes: “No time in all the Twelve Nights and Days is so charged with the supernatural as Christmas Eve… many of the beliefs associated with this night show a large admixture of paganism.” He showcases an impressive list of traditions from all corners of Europe connected with the Christmastide within this volume, which has association with ghosts, dead revisiting their folks, supernatural and magic; associations, which in one way or another having paganistic roots.

Telling scary ghost stories was a Victorian Christmas tradition, whenever friends and family gathered together during Christmas season. In Old Christmas: From the Sketch Book, published in 1875, Washington Irving makes the following observation about this tradition while describing the Christmas Dinner.

When I returned to the drawing-room, I found the company seated round the fire, listening to the parson, who … … was dealing forth strange accounts of the popular superstitions and legends of the surrounding country… …He gave us several anecdotes of the fancies of the neighbouring peasantry, concerning the effigy of the crusader which lay on the tomb by the church altar… …From these and other anecdotes that followed, the crusader appeared to be the favourite hero of ghost stories throughout the vicinity…

So how did this fascination towards narrating spine chilling tales of evil during the time of Christmas originate? In Christmas And Christmas Lore published in 1923 by T.G. Grippen we can find the following reference to the tradition of reciting ghost stories on the Christmas Eve, in England.

“Notwithstanding these imaginary terrors, Christmas has long been accounted, in England at least, the most fitting season for ghost stories.”

Grippen analyzes the proverb “Talk of the Devil and he’ll appear” and points that the root of this tradition lies in the folk belief that, speaking about the evil beings gives them power to perform mischief. He observes that despite this fear of the ‘devil appearing’, there is a strong urge in human beings to talk about or listen to tales related to “ the night side of the nature”. The sacredness associated with the Christmastide – and especially the Christmas Eve – gave them a safe time-frame to indulge in having conversations about ghosts and spirits, without fear.

“… we understand somewhat of the fitness of Christmas-tide for conversation about the shadowy side of the Universe of being. At other times there might be danger in talking too familiarly of ‘fiends, ghosts and spirits that haunt the nights’; but at Christmas the power of malignant spirits was so neutralized by the mystical presence of the Christ-Child that curiosity respecting them might be safely indulged.”

From the mid-1800s various publishers in England also contributed to the popularity of this tradition, as they started to publish special Christmas issues of magazines and serials containing ghost stories. The Old Nurse’s Story by Elizabeth Gaskell, A Christmas Carol and The Signal-Man by Charles Dickens and The Body Snatcher by Robert Louis Stevenson are some of the famous Christmas time ghost stories, which made their first appearances in Christmas issue magazines.

Kenneth Mathieson Skeaping

The 1891 Leadenhall Press edition of Told After Supper is lavishly illustrated, and has about a hundred beautifully done illustrations by the Victorian era painter and illustrator Kenneth Mathieson Skeaping. There are numerous pen and pencil drawings, chapter heading decorations, drop caps and full page illustrations within this edition and they contribute nicely to enrich the overall mood of the narrative.

He explained that the ghost of all the tobacco that a man smoked in life belonged to him when he became dead. He said he himself had smoked a good deal of cut cavendish when he was alive, so that he was well supplied with the ghost of it now.

I observed that it was a useful thing to know that, and I made up my mind to smoke as much tobacco as ever I could before I died. I thought I might as well start at once, so I said I would join him in a pipe, and he said, ‘ Do, old man ‘; and I reached over and got out the necessary paraphernalia from my coat pocket and lit up.

Born in Liverpool, England, UK in 1957, Kenneth M. Skeaping also illustrated Jerome K. Jerome’s The Devil’s Acres and On the stage – and off: the brief career of a would-be actor.

Told After Supper, is a recommended reading for all fans of Jerome K. Jerome and for those who love light entertaining tales from the Victorian Era.

– Pramod S Nair